Hi, it’s me, and I need to start off by saying DON’T SPOIL THE TED LASSO FINALE FOR ME. We watch with our son, Thomas, but he’s had to work at his stupid job and go to his stupid school, and since he’s a stupid boundary-setter, we haven’t been able to watch it yet.

Bryan says, What a Lasshole.

While we’re waiting for Thomas to finish being responsible, I’ve been in the garden, as per usual this time of year. Yesterday I moved my Salvia Hot Lips from a shady spot to a sunnier spot, and replaced it with a shade-loving Hellebore. Both will be happier now that they found the right environment for their needs.

What’s that you say? There’s a metaphor in there? Why yes, you’re correct — I also believe the garden is full of life lessons.

I’ve long been a person who feels like things will always be this way — this, being whatever it currently is. I get paralyzed making decisions because I ascribe utter permanence to my choice, when rarely is there a decision that is truly permanent.

But in the garden, I’m always moving stuff around. I change my mind, or I plant things too close together, or like the Salvia, they just need to find a better spot in the sun. I’m working on living my life with no regrets, because most things can be re-decided.

Hey, so I asked my friend Kim to share a story with you. She’s the bee’s knees and is a regular at our Thursday Fire Nights.1 I trust that her story will resonate with you in some way — it does me. I’ll be back next week.

Until then,

Jen

p.s. If your email client cuts this off before the end, you can click here to read it online.

Fuck Those Guys, Wear the Swimsuit

Hi, I’m Kim. Most of my earliest memories involve playing in the water.

Cousin Jimmy (first, once removed) carrying me across Great Aunt Karen’s pool

Playing at Pop’s cabin on Lake Hiawatha

The Rockaway River flooding so high that we could canoe in our yard

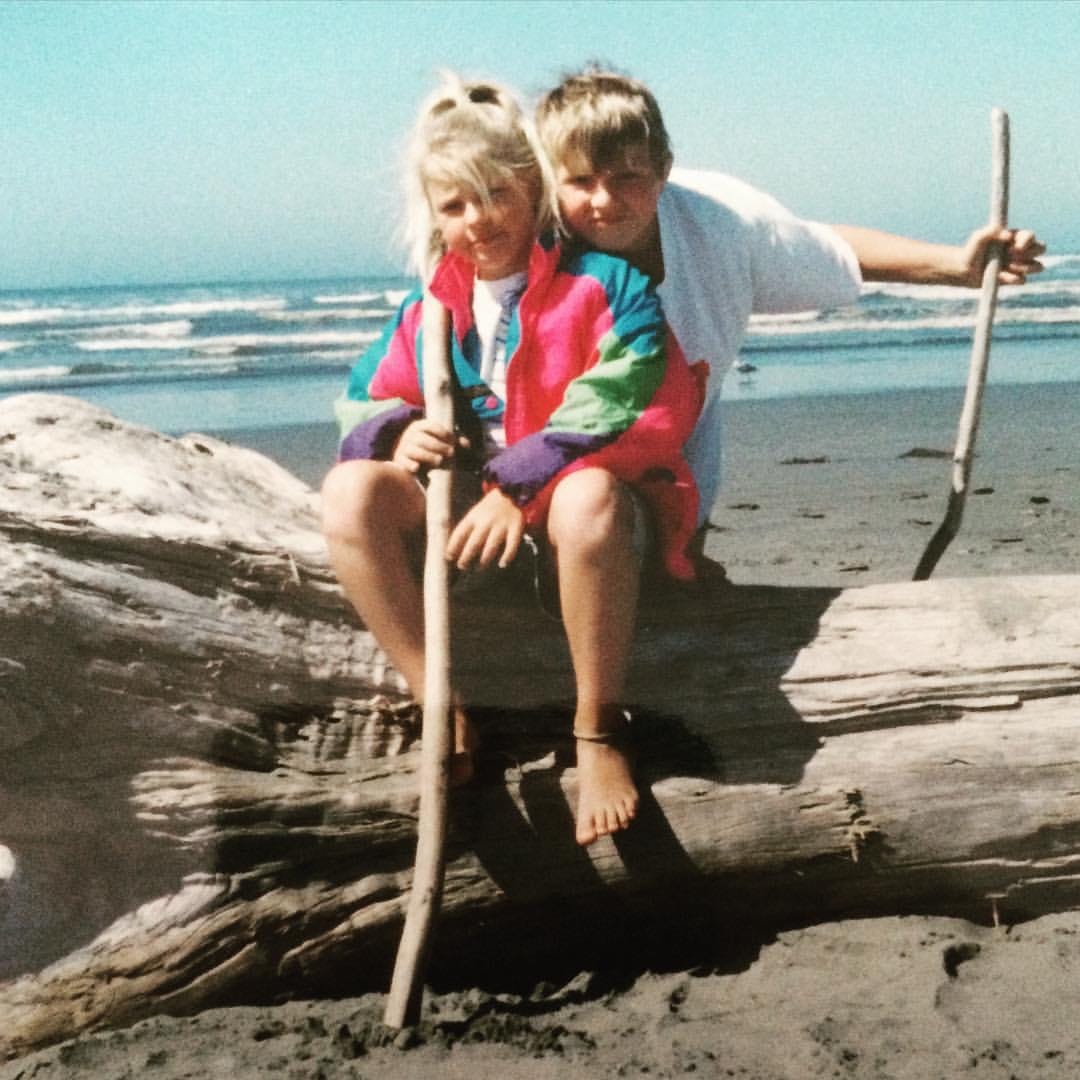

In 1990, my family moved from northern New Jersey to Sequim, WA (pronounced skwim) where my older brother and I rapidly transformed into feral Goonies-like children.

My childhood revolved around being in and around the water.

Summers were marked by camping trips to the Salish and Pacific beaches on the Washington coast where my brother and our friends would hit the beach in the morning while the marine layer was still thick, and play all day in the waves and beach rivers. In August, I would go to summer camp on Lake Crescent and play in the 55º water until camp staff made me get out because I was turning blue. For the rest of the year, we were at our local pool a few times a week.

I am autistic and have sensory processing issues, and being in the water is one of the few ways I know to turn down the volume on the world around me. It was a place of peace and relief for me.

Until One Day

When I was 7 or 8, a friend invited me to her birthday party. The other girls called me a tomboy (I hate that word) and decided it would be fun to do my hair and makeup.

Afterward, everyone wanted to do a polar plunge into my friend’s pool, but it was so cold out I hadn’t even thought to bring my swimsuit. My friend had spare swim suits that fit everyone else—but nothing fit me. I wound up in a purple Speedo that barely went on my body. I was suddenly acutely aware of my divergent body size, something I had never considered before. I put my jammie shorts on to hide the fact that my swimsuit was so far up my ass I could taste it.

They posed me to take a Polaroid, telling me to suck in my belly, otherwise, the boys wouldn’t like me, and positioned my hands so awkwardly to hide my belly. They told me to smile—but not my normal smile—a pretty one that showed my teeth—so I pushed my face past my normal autistic Mona Lisa smile, and this photo was taken.

And just like that, a little root sprang up and my body size became connected to my value and worth.

Over the years, I learned my body was wrong in a thousand different ways.

I learned it every time I climbed out of a pool or onto a dock and other kids shouted “Beached whale!” and when I jumped in, they yelled “Tidal wave!” I learned it when adults commented disparagingly on their own bodies—or mine. I learned it with every fat joke in movies and TV, and from friends. I learned it every time a video of a fat person simply existing went viral.

I learned it over, and over, and over again until one day in college when I was wearing a swimsuit, I walked past a man who laughed and said, “No one wants to see that.”

It all became too much.

I spent the next decade avoiding swimsuits as much as possible.

This meant avoiding the water—one of the few places I felt at peace in my own skin.

In my early 30s, I spent time contemplating when I last felt like I knew who I was, still unencumbered by others’ opinions of me. This introspective journey had me talking to God a lot—praying, I suppose—but more like self-hate-filled laments begging God to change my body because nothing I did worked. No amount of food restriction, endless walking, or secret bedroom workouts so no one would see my gross body move, worked.

God met me in a way I could not have predicted. Rather than changing my body, beliefs I had been taught since childhood began to fade away. Like the belief that fat bodies were bad and evidence of moral failing.

I began to trade the beliefs of American culture—which idolizes thinness and sameness—for what the God I believe in actually says about me, that I was made good—wonderfully made—beautiful—loved, in this body, right now.

Slowly, I returned to what I loved.

I started asking myself, “What would 10-year-old Kim do?”—and then did those things. She wanted to wear high-top sneakers and backward hats and play ice hockey. I joined a hockey club with no experience at 33 years old. When the pandemic shut my first hockey season down, I bought a cheap kayak and inline skates—a hobby I loved as a kid. (I did not use them at the same time.)

I was re-learning how to do the things I wanted to, despite what the world so loudly says about bodies like mine—that we don’t belong, or are somehow unworthy of access—that we have to lose weight to be able to engage in sports and outdoor spaces.

(A man on Twitter once told me I shouldn’t have access to a life jacket because fat people in the outdoors are more likely to die. Bitch, people who don’t wear life jackets kayaking on 55º water are more likely to die.)

As the shame started to flake away like crusty old toxic lead paint that was losing its grip on the beautiful nobody-knows-why-they-covered-it-to-begin-with hardwood beneath it, my world began to expand back into the world that my younger self explored so joyfully and carelessly. The more I disentangled from the anti-fat biases that the world held against me—and I had learned to hold against myself—the more I was able to move my body freely and with joy.

When I started kayaking, I remembered how much I loved the water—and that 10-year-old Kim wanted to surf.

Despite playing in the ocean unsupervised as a child (and somehow surviving?), I never really learned how to swim. I knew how to not die in the water—this is not the same as knowing how to swim. Since surf camps required basic swimming skills, I signed up for swimming lessons at age 35.

I realized, horrified, that I would have to wear a swimsuit—in public. And in order to surf I would need a wetsuit—basically a neoprene sausage casing.

I practiced swimming at my local community pool—in a swimsuit—in public. I was terrified. I could still see people’s judgmental eyes looking over my body—and occasionally hear their spoken comments. But this time, fuck those guys. Thirty-whatever-year-old Kim and ten-year-old Kim have teamed up to be extraordinarily resolute in not allowing jerks to steal our joy anymore.

Last summer, at age 36, I started learning to surf.

I suck at surfing, it is a hard sport—but I love it so much. The first moment I felt the energy from a wave transfer up through my board and propel me forward, I knew I was exactly where I belonged—where I always belonged—in the water.

The journey is not all rainbows and puppies and butterflies. There are still systemic issues that keep large-bodied people out of sports in general—and especially water sports. There are currently no companies selling wetsuits for plus-size women in the US.2 Quality, size-inclusive *active* swimwear is still extraordinarily hard to find.

I still get disgusted and judgemental looks from people any time I don a swimsuit or my wetsuit in public—especially if my midsection is exposed—but, again, fuck those guys. Finding other equipment—like surfboards or lifejackets/PFDs—for heavier or larger bodies is still hard, and we’re likely to still deal with bias and discrimination when we shop for those items.

There are also still a lot of individually-held anti-fat beliefs and biases out there that lead to individuals spouting bullshit online and in person at fat/large-bodied people—and especially fat women. There is still a pervasive and loud collective social voice screaming that we don’t belong, and are unwanted in those spaces.

But, seriously, fuck those guys—and let’s change it.

For the last few years, I’ve been dedicating time to change it.

A lot of change comes from simply talking about it—something I do on my MoveFatGirl Instagram account.3 I started it with the thought, “I’ve never really seen bodies like mine promoting engagement in sports and outdoor play that don’t pair it with weight loss goals—what if I could be the representation that I so desperately needed for younger women in similar bodies?” It is still terrifying to put myself out there like that (and like this), but running that account has given me a community of people who are all heading in the same direction—toward inclusion for fat/large-bodied people in sports and outdoors.

I’ve made friends with badass women who are creating inclusive outer and swimwear, and they invited me to design my own swimsuit. It’s in pre-order phase right now.4

I got to face some fears and pose and tell my story for Tommy Corey’s photo book featuring 100 diverse outdoors people.5

I’m currently dreaming about filling the void in plus-size women’s wetsuits, opening water access to the other 68% of American women who wear a size 14+. (Lowkey if you want to fund this endeavor, let’s talk.)

Change is possible.

We know this because change is happening, but there are still systemic barriers and people who perpetuate them through anti-fat beliefs and biases.

10-year-old Kim is pretty well integrated with 37-year-old Kim now, and we do what we want—regardless of what the world says we can or cannot—or should or should not—do, or be, or wear.

So still, again, and forever—fuck those guys and wear the swimsuit.

Your Turn

Several shows had finales this week — Succession, Somebody Somewhere, and Ted Lasso are three I’m aware of. Have you been watching these or any other good shows?

If the 10-year-old version of you could see the Today You, what do you think they would say about how things are going?

If this story resonated with you in any way, share the love and let Kim know in the comments.

I (Jen) wrote about Thursday Fire Night here:

Welcome to the House of Barbecue

Today’s post is the 3rd and final in a 3-part series on my life in community. If you need to catch up, you can read the first one here and the second one here.

I (Kim) had to custom order a wetsuit at a much higher price than ready-made suits to have access to the cold water here in the PNW.

Visit Kim’s awesome Instagram account, @MoveFatGirl.

See photos and read about the swimsuit Kim designed.

Read about Kim’s participation in the All Humans Outside project.

SUCH fabulous words - thank you so much, Jen and Kim!

♥️ Post read: check.

♥️ Round of spontaneous applause: check.

♥️ Life affirmed: check.

Yeah. Fuck those guys. Glad to know ya, Kim! ♥️